to be loved is to be known

magritte's 'the lovers ii (1928)' & klimt's 'the kiss (1907)': on being a mosaic of people we love and knowing when you love someone

[if you like this essay, please consider upgrading your subscriptions because my essays are usually for paid subscribers! my summer plans are to write a lot of rabbit hole essays on arbitrary research topics or literature, film, paintings, linguistics because i think the world gets better when people write essays. you can check out two of my favorite essays below]:

The thing about spring is that you’re never aware of its arrival; it is only when you’re in the heart of a picturesque flower field, or hear songbirds at your windowpane, or when the sunlight feels less ephemeral and more eternal, that you realize the permafrost sadness of winter has finally thawed. Suddenly, you have eight months of being alive again, until the blue gray melancholy seeps into your bones, casting shadows that are almost as long as the endless days in which the sun dips below the horizon as early as four in the afternoon.

Winter, by contrast, is marked by its colorlessness, from the gray nights to the blinding white glare of the snow. It forces you to retreat inwards, seeking a semblance of life from within. It’s selfish in that regard, the cold and darkness will puppeteer you into wallowing, stretching moments into millennia between each second. I think that’s why the incandescence of spring has always felt too brief for me, especially because I rarely recognize springtime until it’s five months into the year and the hourglass is nearly empty by the time I am done dealing with winter’s stubborn aftereffects. A signifier that I have come out of my winter hibernation is when I turn my thoughts inside out and start thinking about the people around me—what I mean to them, and what they mean to me in return.

My loneliest moments, the quiet interludes unfolding between sunrise and sunset, eclipses seasonal boundaries. So in the few weeks where spring too easily yields to summer, from the tail end of May into early June, I find myself thinking about what it means to love someone, and what it means to be loved in return. It’s the sort of optimistic rumination that can only exist when you know that in a few hours, the world will fill with pastel again. Love is too often conflated with romantic affection, becoming a metonym for desire or attachment or yearning. But I think that at its core, loving someone, no matter romantic or platonic, essentially means the same thing.

In my loneliest moments, I like to imagine myself as a patchwork quilt of everyone I have ever loved, and everyone who has loved me. My room is a museum, or graveyard depending on how you look at it, of miscellaneous trinkets I have collected because the people I love once liked them. And at the heart of all that is a box full of handwritten letters I’ve ever received in one of my drawers—the earliest one is from my grandpa when I was three years old and living in England, the latest one is from my best friend a few months ago. I find comfort in keeping record, writing things down with pen and paper, taking solace in that fact that that I am who I am because of the love I’ve received.

Maybe it’s a selfish pursuit of emotions, to coalesce and distill a nebula of love into one thought, but I’d argue that essentially, that is what we are and why we exist. Without trying to sound overly philosophical or didactic, I’ve come to see it as a simple paradox: to love someone is to know someone, and to know someone is to love someone. The root of the causal dilemma shows how innately the two are tied to each other, that love is born of understanding and understanding is born of love.

Perhaps one is because and one is despite; you love someone despite understanding them, you understand them because you love them. Or maybe it’s because in both circumstances, depending on how empty or full you see the glass. Either way, whether the love is romantic or platonic or familial, a foundation of unconditionality is always bound with the commitment of loving someone.

This reflection arose from a conversation I had with my friend a few weeks ago1. She had just come out of a very long and painful breakup, a protracted process she described to me as ‘perpetual purgatory’. Naturally, we began a typical post mortem examination of her relationship over the next few days. She wondered why it hadn’t work out if they loved each other, even through conflict and even (or so he claimed) until the end. I’m sure as with all breakups there are two sides if you search hard enough, but as with all close friendships, I found myself becoming very unsympathetic to her ex’s side as the conversation wore on. I told her this as carefully as I could, as trying to give advice or an opinion about your friend’s relationship as a third-party-but-not-really sometimes feels like walking blindfolded across a minefield.

When she asked me why, I struggled to articulate my thoughts, why I thought that he didn’t truly love her despite his claims. Ultimately, I realized that it simply had to do with the fact that he did not know her as well as he claimed to. Had he truly known her, the said conflict between them would not have even started. Without going into too much detail, he had been upset about a small issue and had let it fester for a month instead of bringing it up with her immediately, letting the issue grow into a creature of its own until it seemed insurmountable. And eventually, an issue caused by miscommunication had morphed into ammunition and an ace up his sleeve that he wielded liberally to claim the upper hand in their relationship.

It stops being a relationship then, I told her. And if he knew you as well as he claimed that he did, he would have known the issue was miscommunication to start with. He let it become something it originally wasn’t. Yet, because he persistently insisted that he did, in fact, love her—and apparently more than she loved him—we found ourselves dissecting and rehashing and talking about how we can really tell if someone loves you. Is knowing someone truly the crux of the intersection between love and everything else? Does heartbreak stem from the realization that someone doesn’t know you well enough, so that means they didn’t truly love you?

She later told me that the catalyst for her that broke her out of the relationship for good, actually came from something I had told her that had happened with a friend. A month back, I said something pretty horrible in a drunk moment that I didn’t even mean. The regret of it barreled into me the next morning in an hungover haze and I cried, apologizing profusely. In return, he told me that there were no hard feelings, because he knew when I meant things and when I didn’t. And true to his word, he never brought it up again. That’s all love really is, she concluded, it’s nothing complicated or grandiose, it’s just about knowing someone well enough to understand them. In short, it’s not about truly knowing someone, it’s about knowing them well enough to understand things you don’t know about them.

I don’t know if it’s possible to be able to fully know anyone, which poses the question of whether or not it is possible to be able to fully love anyone—does this mean that all love is blind? That love is not about knowing someone, but it’s simply about blind faith, entrusting someone by letting them hold your heart in their hands, and believe that you ironically know that they will handle it with care? That’s why falling out with close friends and fighting with your parents and breakups feel like a thousand paper cuts, because it’s not only about losing someone important in your life, but also the betrayal and sinking feeling in your gut that perhaps you did not know them as well as you thought you did. Or they did not know you as well as you thought you did. So did you truly love them? And did they truly love you?

Whenever I think about love, and I guess romantic love in this specific context, I always think about The Kiss by Gustav Klimt. It honestly might be because I have love this painting enough to have a large poster of this in my room, but also because the sheer opulence of it, fused with the intimacy and intensity of it, makes it a very memorable painting.

Klimt was a part of the Vienna Secession movement, which was an immediate reactionary coalescence to the city’s growing artistic conservatism (Klimt eventually split away from the group in 1905 during a dispute of whether or not to give precedence and prioritization to artists in the fine arts, as he believed all artists should get equal treatment). By the start of the twentieth century, the art scene in Vienna, which was historically very academically rigid and conservative, was infiltrated by radical creatives such as Klimt himself. The Kiss was painted in 1907 during his “golden phase”, in which he used an abundance of lavish gold leaf in his paintings. Klimt sought to depict intimacy and human sexuality, which was revolutionary and politically charged against the old-guard European art establishment.

In The Kiss the intimacy is outright and inescapable. The couple, locked in an embrace, is covered in blanket of gold, behind a universe of gold. The man’s face is obscured and he is holding the woman’s face, kissing her cheek. There are no defining features in the background, perhaps symbolizing the immortality of the couple’s love; time and space is an illusion and not included in their current reality—after all, love, emotional metamorphosis, transcends all of that. The world quite literally falls away, crumbles beneath them, when they are together. Klimt’s paintings during this time heavily reflected and were inspired by Byzantine mosaics dating back to the 6th century. Mostly used in religious settings, Klimt’s adoption of this style equates love to a religious reverence, the size of the painting itself akin to an altarpiece.

To love is to be known, and in this case, Klimt seems to be implying that all they know is each other.

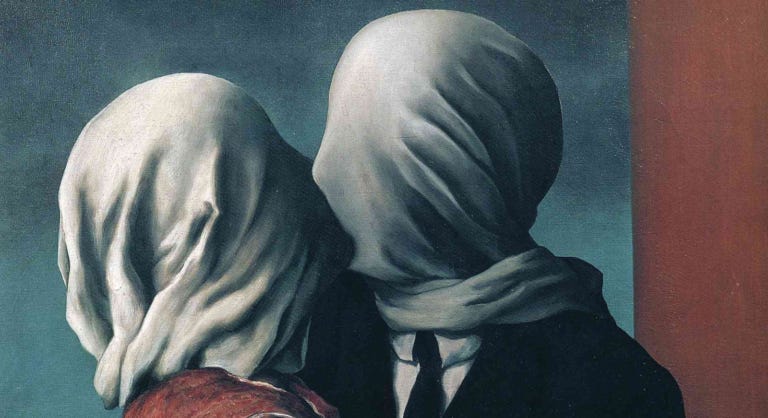

However, a counterpoint that yes, you can love someone fully and blindly, can be seen in Rene Magritte’s The Lovers II. Magritte, renowned for his surrealist paintings, makes something entirely plausible feel surreal and alien. One of my favorite paintings of his and one I have on a throw pillow on my bed right now (see below) is The Treachery of Images, which contains a painting of a pipe that has the words, Ceci n'est pas une pipe or the translated English, this is not a pipe. It is a meta-message in a way, much like Diderot’s “This is not a story” story. Magritte’s surrealism stands out among other artists’ works within the movement because he not only manipulates visual assumptions, but also language and symbols.

Some of his works, like The Lovers II, are not truly surreal at all, unlike The Son of Man (the painting with the apple covering the man’s face) or The False Mirror (the painting with the blue sky being someone’s iris). Magritte painted four versions of The Lovers all within the same year, but the second version of it remains the most known. The surreality of it lies in the impossibility and contradictions of it. At first glance, the painting seems to depict a couple locked in an embrace, kissing. Stare at it for a couple more seconds, and you’ll realize that there are a litany of dichotomies within the painting: it feels purposefully framed yet spontaneous at the same time, the two lovers also feel claustrophobically close yet incredibly far.

While there has been much speculation regarding the reason so many of his subjects’ faces are obscured, including the trauma he endured witnessing his mother’s suicide at fourteen, Magritte vehemently disagreed with this. “They evoke mystery and, indeed, when one sees one of my pictures, one asks oneself this simple question, ‘What does it mean?’ It does not mean anything, because mystery means nothing either, it is unknowable.”2 Regardless of the meaning behind the painting, there is something about it that encapsulates the impossibility and paradox of love so well.

Perhaps this is why I’ve loved this painting for so long and I talk about it so often. As I mentioned above, while this does not feel as surreal as Magritte’s other famous paintings and maybe can even be seen as the most realistic, something about it feels so impossible. In the physical sense, you can see the couple is already close in proximity to each other, the white sheet additionally blanketing them from the outside world. But a closer look shows that they actually cannot see each other. It looks like they are kissing, but the white sheet prevents them from their lips actually touching. In short, they cannot see the outside world yet they cannot see each other. This surreal double edged sword has sliced through both ways, yet they seem blissfully unaware of it.

The painting itself is off center and asymmetrical, which feels almost bizarre and jarring in itself because the sheet itself is painted in such meticulous and realistic detail. It is uncentered on purpose, and gives a further impression that this entire scene is so intimate to the two people in the painting that it feels like it was taken right at that moment with no planning or arrangement. There is something deeply romantic about that, I assume, the intimacy that remains despite, in the absence of, etcetera. Despite the sheet, in the absence of vision, despite the spontaneity, in the absence of real and true proximity.

Magritte’s painting shows the paradoxical nature of love, that in order to love someone, you know them enough to be blind. Put that phrase under a cynical fluorescent light, and go back to the initial question. To be loved is to be known, but do we ever really know someone? Love doesn’t change that. At the end of the day, loneliness is not a feeling that simply disappears because you are in love or intimate with someone. The couple is under the cloth; we can see them but they cannot see each other. We consciously choose to hide traits about us, maybe as a form of self preservation, under the cloth, beyond the reaches of peripheral visions. Despite their closeness, the painting does not evoke a true sense of romantic passion. The blue background is a sharp contrast to Klimt’s gold background, even color symbolism shows that one represents melancholy and the other represents enduring love.

However, under the warm candle glow of romance and optimism, The Lovers II could also denotes the universality of love. We fall in love with someone without knowing who they are—they are strangers one second, and then someone you think you could spend the rest of your life with the next. Like the two people under the sheet in the painting, you don’t need to see the person at all times to know what you feel. You can see someone clearly even if you’re not looking at them, you know that you love them even with your eyes closed. And you know them enough to trust that they can see you when they’re not really seeing you either. Maybe this is the reality of loving someone: blind faith as you walk side by side as strangers.

Does one painting more accurately describe what it means to love someone than the other? I don’t think so.

Love is a kaleidoscope within itself, multifaceted in its brilliance, and I always affirm this by thinking of myself as a mosaic of everyone I’ve ever loved. I love tomatoes a little more than I used to because of a poem my best friend wrote. I paint landscapes because that’s what my grandpa on my dad’s side used to paint before arthritis froze his fingers. I love the color blue a little more than I used to because it’s my other best friend’s middle name. I love the spring because my grandpa on my mom’s side has always recorded the first bloom of every year in his frazzled leather bound notebook. I put another swirl in the swoop of the capital E when writing my name because my middle school best friend, who I no longer speak to, wrote it like that for me on a birthday card. I love long classics because my friend and I used to read one together every month. I accidentally say noooodles because my little sister gets excited whenever she eats noodles and says it like that. I have my mom’s eyes and my dad’s nose. My face is a topography of generations of people who have loved each other.

If you loved someone, even for a little, it’s because you knew them. And if someone loved you, even for a little, it’s because they knew you. The knowledge of that remains eternal.

Postcards by Elle is a reader supported publication. every week, i send out a weekly postcard, which includes a list of everything i read (books and articles) and watched (movies and video essays) that week. to support my work, please consider upgrading your subscription! that way, i can have the time to produce content i love, which mostly just includes rabbit hole essays on niche topics i hyper-fixate on and research. or recommendations of all kinds.

here is my paid subscriber series for June! the first will be posted on June 3rd.

on that note, the actual postcard (with article links and all) will be posted on tuesday! it’s a long overdue on-the-shelf episode featuring , so be excited!

i have permission to write about this!! i promise i’m not just airing my friends’ personal affairs in public. i love u if ur reading this <3

https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79933

as someone who never really understood why i did not feel love for my parents but i did feel love for my closest friends, this was such a good read and i’m glad I didn’t procrastinate reading this like I do with a lot of other things 😭 thank u for posting 🤍

obsessed with the way you write! such thoughtful approaches to analysing art, not just academically but personally too <3 (seeing the kiss in person was astonishing and I totally understand the urge to get a full sized poster of it)