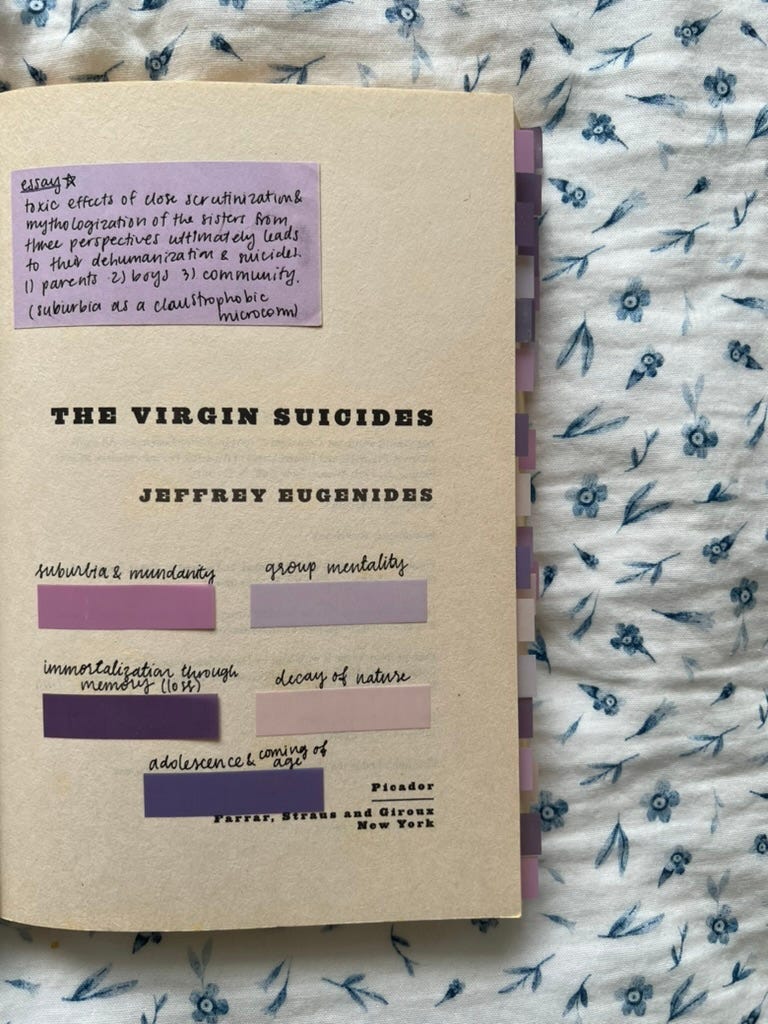

the virgin suicides

jeffrey eugenides' 1993 novel: on mythologizing the lisbon sisters, societal confines, and humanizing girlhood

"Obviously, doctor, you've never been a thirteen-year-old girl.”

I first read The Virgin Suicides in my freshman year of college for an English class called Girlhood. It was the only book on the syllabus written by a man, and I remember being skeptical about whether or not a man could truly portray the struggles and nuanced details of what it meant to be a girl. Shockingly, this, along with Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, ended up becoming my favorite book I read for that course.

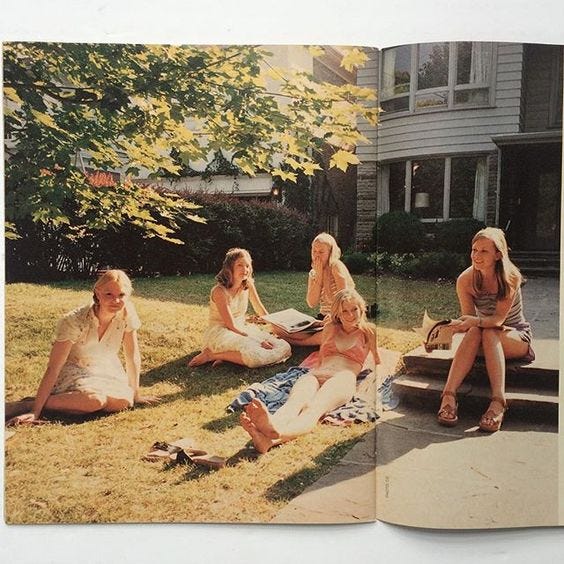

The Virgin Suicides, in essence, is horrifying. The thing I simultaneously love and am terrified by is the flinchingly disgusting atmosphere that Eugenides builds in his book. Amid the lyrical beauty in the prose, there is an underlying sinisterness, an impending sense of doom. Everything feels sticky, humid, and suffocating—from the insular, mass-produced homes in the suburb where the sisters live, the claustrophobic and uniform male gaze, to the physically decaying neighborhood covered in dead flies and a rotting smell.

On the morning the last Lisbon daughter took her turn at suicide—it was Mary this time, and sleeping pills, like Therese—the two paramedics arrived at the house knowing exactly where the knife drawer was, and the gas oven, and the beam in the basement from which it was possible to tie a rope.

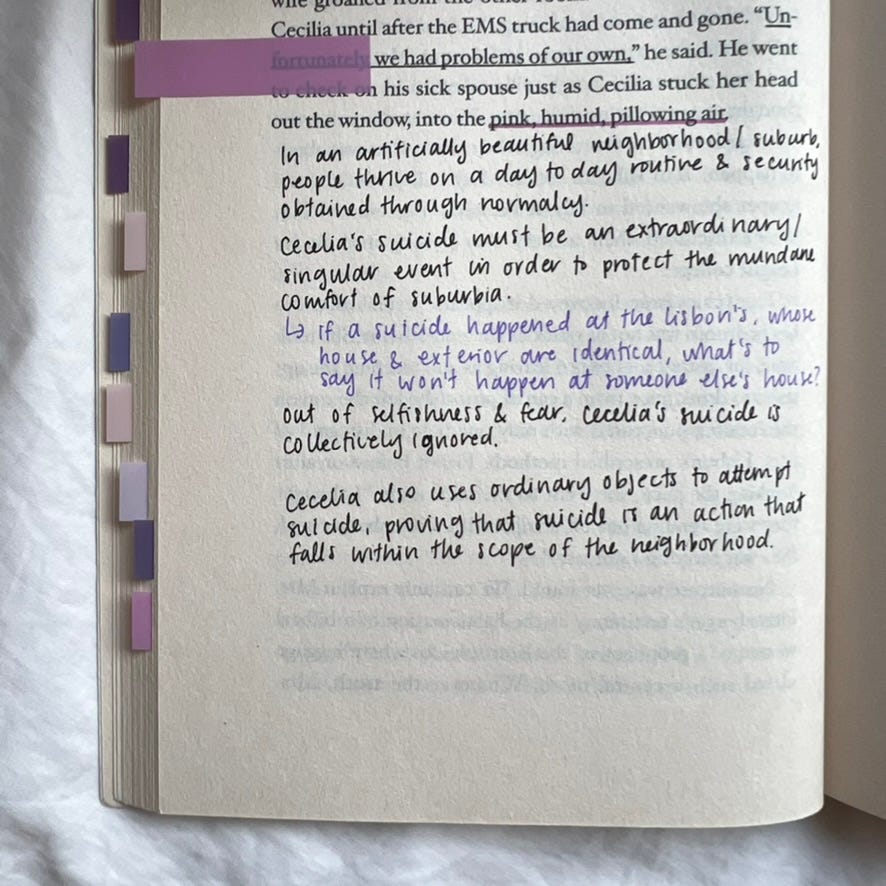

From the very first line, Eugenides gives no room for the reader to ponder or hope for the girls—we know how this book will end, and we, as spectators, will have to witness the end of each one of their stifling, surveilled lives. For two hundred or so pages, we are roped into living in this small town, suffering the same fate as the five Lisbon sisters. The Lisbon girls' version of their society is a small microcosm of a suburban setting, where everyone is expected to be as identical as products on a conveyor belt in a factory.

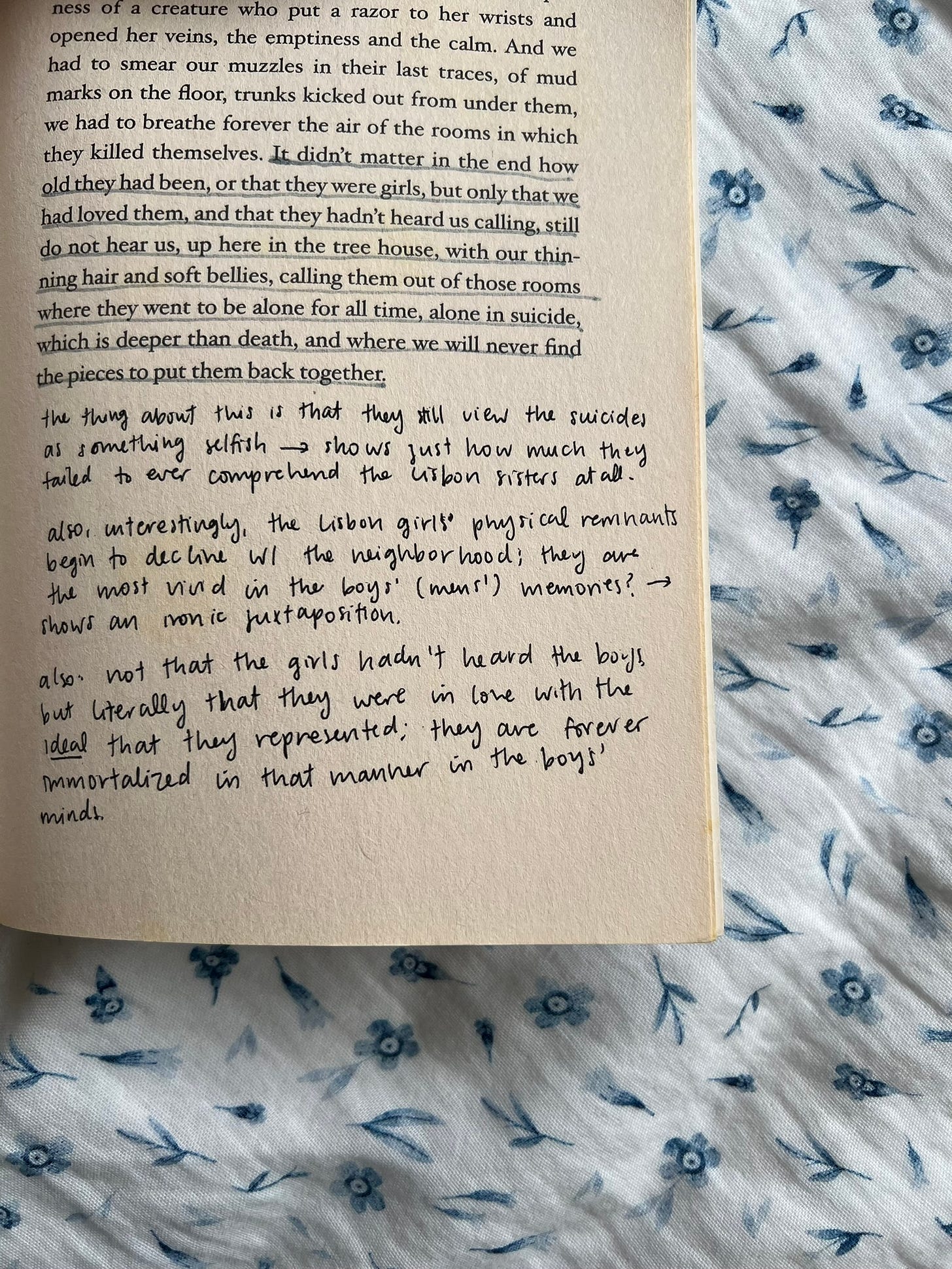

The Virgin Suicides is retrospectively narrated through the eyes of the neighborhood boys, now well into adulthood, who are still hyper-fixated on the girls. Every moment of the book is portrayed through the paradigm of the boys’ unsettling pluralistic first-person narrative. Reminiscent of a Greek chorus, these boys still view the Lisbon sisters and their suicides as a myth, a mystery that has yet to be solved. Ironically, while it is the boys that are unnamed and referred to as “we”, they view the Lisbon sisters as one entity, refusing to individualize them.

In a 2013 interview about the book, Eugenides talked about the 1993 movie adaptation, directed by Sophia Coppola (which has now become a cult favorite and also was added to the Criterion Collection). He said,

With a book like this, no one should really play the characters, because the girls are seen at such a distance. They’re created by the intention of the observer, and there are so many points of view that they don’t really exist as an exact entity. The way to do it would be to have different actresses playing the girls at different times, depending on who’s talking about them. That would be too avant-garde, but closer to the spirit of how I wrote the book. I tried to think of the girls as a shapeshifting entity with many different heads. Like a hydra, but not monstrous. A nice hydra.

The dichotomy between the way the boys viewed the sisters and the reality of who they were is almost painful. They do not see them as actual humans, even calling them "mythical creature(s) with ten legs and five heads" at one point, when the sisters were simply girls who never got the help or love they needed. Unbeknownst to the boys, it is them that immortalizes these girls and makes them into something that they are not. In a way, not only have the Lisbon girls perpetually remained adolescents, but the boys have as well, unable to escape the clutches of their infatuation with girls and their subsequent suicides.

One scene worth examining in detail is the only actual encounter one of the boys has with a sister. After holding the girls at arm’s length and on a sky-high pedestal throughout the book, Trip Fontaine takes Lux, the “brashest” and “most compelling” sister, to Homecoming. A nightmarish concoction of imagination fueled by sexual desire and the male gaze crescendos to a final climax when Trip and Lux have sex on the football field. Lux breaks down into tears, saying, "I always screw things up. I always do", and later, Trip tells the boys that he "really liked her, (but he) just got sick of her right then". In the only instance where a Lisbon sister is humanized instead of hyper-idealized and objectified, they lose interest.

In a way, the boys’ treatment of the sisters is not only hyperbolic and emblematic of teenage boyhood, but it is also a byproduct of the community that they live in. The Levittown-esque neighborhood is shrouded in suburban domesticity, its obsession with perfection the ultimate factor that puts the girls in a mold they cannot escape. The town is desperate to keep its shiny and beautiful facade, removing any vestige that would indicate otherwise.

Basically what we have here is a dreamer. Somebody out of touch with reality. When she jumped, she probably thought she'd fly.

When Cecilia jumps out of her window and impales herself on the white picket fence, they are quick to remove the fence, disguising this as a way of helping the Lisbons. However, the truth cuts deeper and more sinister than this. In a homogenous neighborhood that encourages manufactured conformity and condemns individuality, this is a terrifying ordeal—if a fence, symbolic of the town’s immaculateness and identical to every other house’s fence, becomes tainted with blood, what’s to say that it won’t happen at someone else’s house? Her suicide attempt is seen as an epidemic that must be quarantined.

In a similar vein, when word spreads that the elm trees surrounding the neighborhood are dying due to an infection, the community is quick to issue all elm trees to be cut down. The analogy between the sisters’ suicides and the elm trees is crystal clear, and the representation of them as ephemera is a juxtaposition with how the boys describe the ethereal beauty of the sisters.

In a way, The Virgin Suicides more or less captures the feelings of adolescence through both the girls and the boys. The yearning to be understood while grappling with the fact that there are a plethora of things that we don’t understand yet. Indulging in idolization and obsession, crushes and unrequited love. Trying to understand ourselves and the people around us at the same time while facing expectations and sticking to standards.

It didn't matter in the end how old they had been, or that they were girls, but only that we had loved them, and that they hadn't heard us calling.

In the end, death is the only way the girls can be humanized: after all, death is the ultimate flaw of life. After the death of the sisters and the decay of the neighborhood, the boys are still unable to move on past the tragedy of five girls, perpetually frozen amongst the white fences and manicured lawns. Perhaps they had loved them because they didn’t know what love was, and never will within their deluded sense of nostalgia. But their calling will forever be an echo into the abyss, a grasp into an eternal darkness.

I actually read this book only last year. I live in India. The treatment of the girls and especially the incident you pick out of desire that turns into disgust once it is actually being fulfilled, reminds me of the fantasy-imbued misogyny in south Asian culture. Here the male gaze is predatory, full of adulation and lust but simultaneously disgusted by the idea of women as sexual beings. The book was, for me, a window into my own adolescent experiences in small town India.

This book is my next read. I love your essay today. We do love cult books about girlhood. 💌💕