intro to 20th century classics reading syllabus

an introduction and three month syllabus for 20th century modernist literature

I’ve been making reading schedules for the last six months based on theme and season, and I thought it would be fun to ask some of my reader friends to make reading syllabi for themes that they are much more well versed in than I am. For this one, I asked Griffin (

), who runs the newsletter . Griffin is my best friend and one of my favorite people in the whole world! I keep forgetting that I know him from Substack because I’ve spent so much time picking his brain re: literature in person, and of course, being upset and disappointed that he voluntarily reads Pynchon. But thank god he has a newsletter (a fantastic one you should absolutely check out) because this way, I get to put him to work and force him to make a syllabus.He is also someone who has largely influenced my reading taste in the last year, especially pivoting my book choices from contemporary literary fiction to 20th century modern classics, which I am somewhat grateful for but somewhat upset that I enjoyed books that I was so sure I would hate. All of his picks below are books that I have either enjoyed or have on my to-read list, so I’m excited to follow along as well.

This also feels like a good time to mention that we are hard at work, planning a joint post on NYRB classics (because that’s pretty much all we’ve been reading in the last few months). Griffin also wrote about his top 10 books way back in November of last year for my on the shelf segment! Check it out here:

Introduction to 20th Century Modernist Literature

(guest syllabus by

)My first real encounter with Modernism was in 2019 and it destroyed my life. I’m being dramatic. I rebuilt, of course. I was a Sophomore in college at the time and had somehow managed to get around the prerequisites for a Senior-level James Joyce class; one day, during my readings, Joyce’s Ulysses attacked me, as if from behind, knocked me out cold and for four months I was in a dream-space with the same refrain on loop in my head, “How is this possible? How was this legal to write?” (and it wasn’t exactly “legal” to write, it turns out — but that’s a tangent for another time), poring over pages upon pages upon pages in my room, pen in hand, in the park, sitting on docks over the lake, reading from lamplight in the corner during family gatherings much to the dismay of one grandparent who was particularly concerned that the university had me reading “nonsense”.

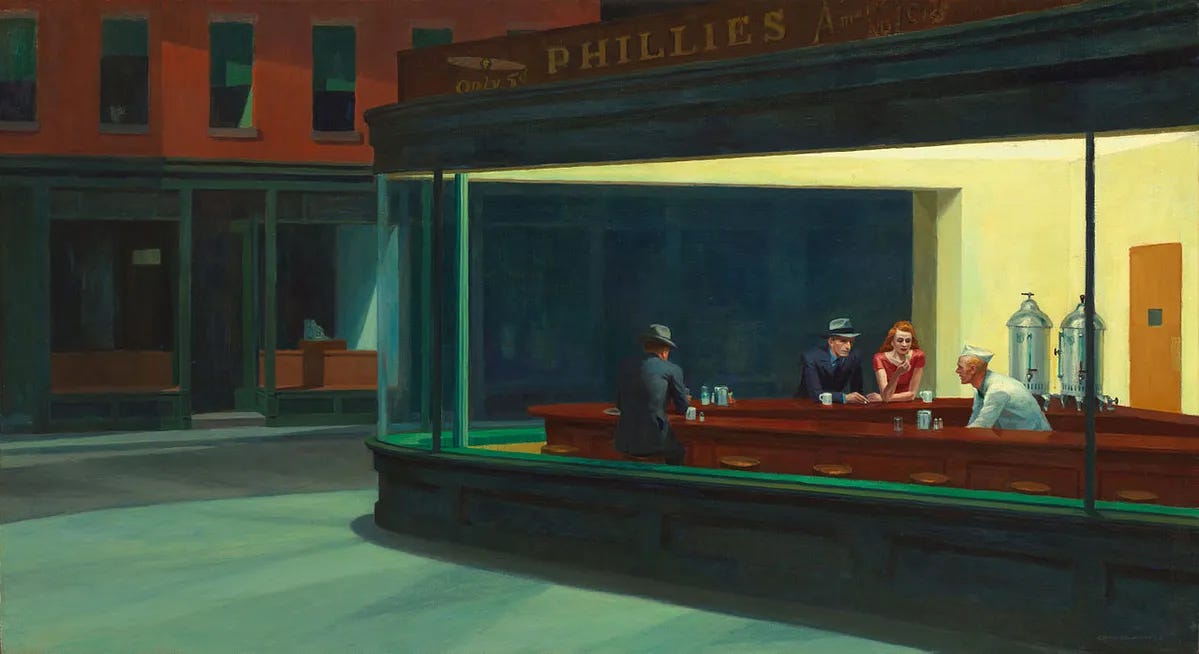

I’m not going to claim to fully understand Ulysses — can anyone? Even on my second re-read (currently ongoing), I’m still putting the pieces together — but then again, a logical understanding comes secondary to modernist texts such as this, or Finnegans Wake, or Woolf’s The Waves, or Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu. Some might disagree with this; certainly there’s a small army of academics worldwide interpreting the material and understanding it with a remarkable and clear, and logical, depth. But my personal love for this moment in literary history is the vagueness, the mystery, the bizarre humor.

Imagine, for a moment, a purely unconscious language: one which perfectly alligns with the linguistic (and non linguistic) mechanisms of your brain thinking, working, sleeping. Imagine you have a book in that language, in your hands, that you could sit with for hours and read, sometimes laugh along with, sometimes pore obsessively over; a language that links the unconscious of the moment at hand to the unconscious of a full life’s arc. There have been times, occasionally, over the last five years as I’ve read as deeply into the modernist canon, where I could see through the words which I was struggling to place into existence in my mind, to find some sort of understanding with them, as if the ink itself had become a portal to something as eternal as the sun and the moon and a wide constellation of stars I never knew existed.

Here’s a snippet of an essay by Virginia Woolf called “Modern Fiction” (month 2, week 2 in the syllabus below) that phrases it perfectly:

“Examine for a moment an ordinary mind on an ordinary day. The mind receives a myriad impressions—trivial, fantastic, evanescent, or engraved with the sharpness of steel. From all sides they come, an incessant shower of innumerable atoms; and as they fall, as they shape themselves into the life of Monday or Tuesday, the accent falls differently from of old; the moment of importance came not here but there; so that, if a writer were a free man and not a slave, if he could write what he chose, not what he must, if he could base his work upon his own feeling and not upon convention, there would be no plot, no comedy, no tragedy, no love interest or catastrophe in the accepted style, and perhaps not a single button sewn on as the Bond Street tailors would have it.”

Here’s an example. At the end of the second-to-last chapter of Ulysses, after the two protagonists, Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus, Odysseus reborn and Telemachus (his son) reborn, Bloom returns home and climbs in bed beside his wife, Molly, who’s faking being asleep. Here’s the description as Bloom drifts off into sleep after a long 737 pages of wandering the streets of Dublin:

Does it look like nonsense to you? It did to me too — though by this point in my first read, I was used to the nonsense. Because it is nonsense, in a way. But nonsense can be useful, especially in art. The trick with the above, in my opinion, is to read it out loud, to yourself, and you can almost feel the emulation of what it means to drift into sleep after a long day of chores and errands, work and dilly dallying around town. And also I can’t help but laugh while reading through the list of fellow travellers: isn’t that worth something? Sure, it may be nonsense, but who doesn’t love a little bit of nonsense now and then?

But then, at the bottom: “Where?”, and there’s a dot. This could be a period — a large period, sure. It could be the Earth… It could be the moon in the sky. It’s on that point that we leave Leopold Bloom forever.

Legend has it that when the first proof copies of Ulysses were being read through, one out of a handful of test reader asked Joyce if he had intended to leave a period hanging at the end of this chapter and Joyce supposedly asked to look at the page, pulling out a pen. He circled the period and continued to draw until it became a large circle. He never explained what this meant. But I think I know. I can’t quite explain the feeling. Whatever the dot expresses, the feeling exists beyond the cold rationality and mechanization that ripped apart the world in the early twentieth century — here’s a startling example of a piece of art intent on reaching beyond that cold rationality. This dot startled me on my first read, I still remember the feeling of first encountering it: I felt suddenly as Alan Shepard must have, looking back on the Earth from the moon, that lonely pale blue dot floating aimlessly in the universe. Except this was made of ink. And suddenly everything I had ever read became the Earth. And here I was, a reader suddenly, starkly, standing on the outside of it all.

Here’s a reading syllabus I put together which can hopefully help understand the transition from the nineteenth century’s murmurings of a changing world with the rise of industrial reproduction (month one) to the beginning of the twentieth century (month two) when artists were grappling with a world having become something new, mechanical, cold, and lifeless. Then, in month three, we’ll take a look at what happened after. I include a number of texts which can hopefully form a tether for us to understand how we got from there to here, a resounding present moment with its own, unique flavor of cold rationality and inhumanity, and its own simmering response to a changing world struggling to be born.