At breakfast, before he ate his single slice of dry toast, my father would sometimes try to pray, but more often he turned to talk to his reflection in the chrome toaster. One morning I heard him ask his own reflection if I would grow into anything more than an ugly prince.

—Yachts, Mark Baumer

prelude

All of us, at some moment, have had a vision of our existence as something unique, untransferable and very precious. This revelation almost always takes place during adolescence. Self-discovery is above all the realization that we are alone: it is the opening of an impalpable, transparent wall - that of our consciousness - between the world and ourselves.

The Labyrinth of Solitude, Octavio Paz

Every month, I’ll be featuring someone’s favorite books so you get to hear from someone who isn’t me. For November, I asked Griffin, one of my best friends, who runs the newsletter

& who I just had a really wonderful time with in person. He is incredibly smart (very intimidatingly so), and is my favorite person to talk about books with, because he is just so well read and has the most insightful things to say about them. In classic Griffin fashion, this post is extremely long, extremely comprehensive, and extremely well written.As always, as I do for my Substack friends, I’ve linked a few of my favorite essays of his in the article links!

1. Frank O’Hara, Collected Poems

“My eyes are vague blue, like the sky, and change all the time; they are indiscriminate but fleeting, entirely specific and disloyal, so that no one trusts me. I am always looking away. Or again at something after it has given me up. It makes me restless and that makes me unhappy, but I cannot keep them still. If only I had grey, green, black, brown, yellow eyes; I would stay at home and do something. It’s not that I am curious. On the contrary, I am bored but it’s my duty to be attentive, I am needed by things as the sky must be above the earth. And lately, so great has their anxiety become, I can spare myself little sleep.”

- Meditations in an Emergency, Frank O’Hara

Let’s start with the greatest offender, my good friend Frank.

Around a year after I started college, I wrapped myself in a puffer jacket and shuddered my way through the gusts of wind coming off Lake Mendota (early February in Wisconsin goes brrr) on my way to a creative writing class in a big cinder block of a building on the lakeside because Creative Writing had just recently become my second major and this late winter walk was my consequence. In a couple of months’ time, Creative Writing would become my only major (to the sound of a hundred sighs in empathy for my sudden lack of employment prospects, the loudest being that of my father) and I still approached it with maybe too much of relaxed, "this is something I do on the side," posture,—and in general, I still thought rather lowly of poetry, thought it was kind of a swindle. Too Instagrammable. Rupi Kaur comes to mind. No offense to Rupi Kaur, she is possibly the best poet in her niche. But I was stupid as a teen and of course, poetry can only be understood after gathering up life experience in your arms and in your apartment.

Sure, I'd read some Dickinson, some Blake, some Whitman— I really enjoyed the 1855 version of Leaves of Grass. I loved Anne Carson and Shelly especially; I remember reading “The Moon” and attempting to write a song out of it in High School. It was (um) not super great… But poetry in general wasn’t something I ever felt much of a desire to return to, to consider much, in a general sense.

My first creative writing workshop was headed by a brilliant poet from New Orleans who I was desperate to impress with my je ne sais quoi: I wrote a two-page single space poem for workshop in the shape of (um) something I'll leave to the imagination here, that left the class, where most of the poems up for workshop were about a soccer match or descriptions of weather, rather dumbfounded. That was the point. It was exactly the reaction I had wanted. I wanted to write reckless poetry, especially in a class where most of the poems workshopped were about soccer matches or new cars.

Clemonce asked me to stay after class. He paused, and asked how long I had been writing for. I said a year and half. He looked taken aback and I don't know if he did this because he was genuinely impressed, if he was just encouraging me on, or both, but our little conversation worked so well towards encouraging me on that after he recommended I read Frank O'Hara's poetry, I beelined straight for the Memorial Library without so much as pulling my jacket sleeves onto my arms, and I found a dusty copy of Collected Poems on the bottom shelf of a cobweb strewn iron bookshelf on the third floor.

I eventually had to buy myself a copy now duct-taped together, scribbled full of chord changes, small notes, underlinings, drawings, etc. I bring this above story up because Frank was my real introduction to poetry. He was the first poet who I felt understood through.

It’s still remarkable flipping through the book and seeing these hundreds of pages of poems delving deep enough into everydayness while folding language like casual origami done with bubble gum wrappers until it becomes a strong enough emotion to make a person fairly drunk.

Frank’s work frightens me in a small way; I’ve always felt competitive enough in my writing to know true genius when I see it. Every poem he’s written has a gut punch somewhere inside of its unraveling, somewhere a hallucinogen in a mixed drink, ecstatic emotions taken by the handful from across the spectrum of your attachments to things like bedrooms, house parties, movie theaters, frying pans, cold sack lunches, etc. etc. reconfiguring them into a life experienced and lived and captured like a polaroid capturing light.

It’s dangerous stuff Frank was working on. It’s a shame he died at 40, run over by a dune buggie, because who knows what he would have gone on to write. He was a fast-burning candle, a flash in the pan, a quick-burning sparkler who loved mundane things like lunch, intimate conversations over drinks, house parties for their togetherness, films for their passion. To my day, Frank's my biggest muse. If I’ve been cribbing from anyone for my substack posts, it’s been from Frank.

So much poetry seems uninvolved in the everyday activities of your life until you find personal evidence to the contrary, that poetry is a distilled passion ready to open wide enough that you can exist inside it for a little while. I also felt this way about Mark Baumer and Danez Smith who both deserve spots on this list but didn’t find their way to the final version, but it’s likely I wouldn’t have found them had I not been recommended O’Hara. And now I’m recommending it forward. To you.

Frank’s also a rare poet in that his poems do actually work like a party trick. Some nights, playing music with close friends, once we’ve exhausted the songs we want to cover, once we've been through the original compositions and the one or two sections of "I just wrote this one the other day", once the night’s become the morning and there are empty drinks and beer cans strewn all over the place, I always find myself breaking out my copy of Frank's Collected, and we can play progressions together and swap off reading lines from the book, flipping around until we find something we like, cracking up, laughing, making up our own lines on the spot. There's an example of poetry as a communal experience. Poetry's real underwater strength is how it can be passed around and shared in real space, not so different from sharing a Spotify link only the songs are sung in your voice and that of the people you love.

2. Collected Fictions by Jorge Luis Borges

“I saw the delicate bone structure of a hand; I saw the survivors of a battle sending out postcards. . . I saw the oblique shadow of some ferns on the floor of a hot-house; I saw tigers, emboli, bison, ground swells and armies; I saw all the ants in the world.”

- The Aleph, Jorge Luis Borges

If you know me, you know I love baffling works of fiction, — and nobody wrote out a narrative puzzle quite like Borges did.

One of his stories seems on the surface to be a book review for a book by an author who had never existed; another is a handful of journal entries by a socialite who discovers a single-lettered volume of an encyclopedia series written for a country that has been thought up by a secret, underground society. These stories feel like small bibliographies and newspaper clippings that line the bottom of a dresser, those which you don’t take note of until you sit down to give them a proper read. All sorts of strange contradictions appear. Something doesn’t quite add up, you think. What’s going on here?

And you begin to wonder if this is not a translation of a copy of a copy of retelling. Who’s editorial hands have distorted the narrative? There are characters in Borges's stories who are written down in the traditional sense, with faces and names, but in a turn unique to Borges’ fictions, there are also fictional editors, rearrangers of narrative, and translators with their own intentions and inclinations. They come up sometimes in the footnotes; sometimes they’re nameless and only exist in the abrupt changes in narrative feel, — the stories have been passed through a wide number of fictional hands, all playing a sort of musical telephone with the text.

3. Agua Viva by Clarice Lispector

“I know that my phrases are crude, I write them with too much love, and that love makes up for their faults, but too much love is bad for the work. This isn’t a book because this isn’t how anyone writes. Is what I write a single climax? My days are a single climax: I live on the edge.”

It has been wonderful to see Clarice Lispector having something of a resurgence in the culture. The other week I saw someone reading Near to the Wild Heart on a bus and what an amazing feeling it was seeing her name in public.

Lispector’s work stands firmly with the great modernist writers, on the level of Woolf or Joyce, Kafka or Beckett. I suppose a big reason she hasn’t gotten her due is because I can’t imagine what a task of a translation it would be to move her words into English from Portuguese, especially for Agua Viva, a book about nothing at all except the bubbling anticipation of words being written.

The book is short, — the New Directions translation is only a mere 88 pages, — but every page is purified and refined like a shot poured neat of very good Mezcal. It’s life water! Agua Vida! Of course, it’s going to make you drunk. It’s her final book and possibly the one she spent the most time on, painstakingly composing the flow and narrowing the scope down to the bare essentials of feeling.

Calling it a novel would be reductive, it’s more of a dance and a breathing exercise. All it asks of you is to breathe through it, - it won’t care if you choose not to, - but if you do choose to enter into these clear blue waters, be aware that you will come out of the experience with a strange sort of buzz lasting at least 72 hours, guaranteed.

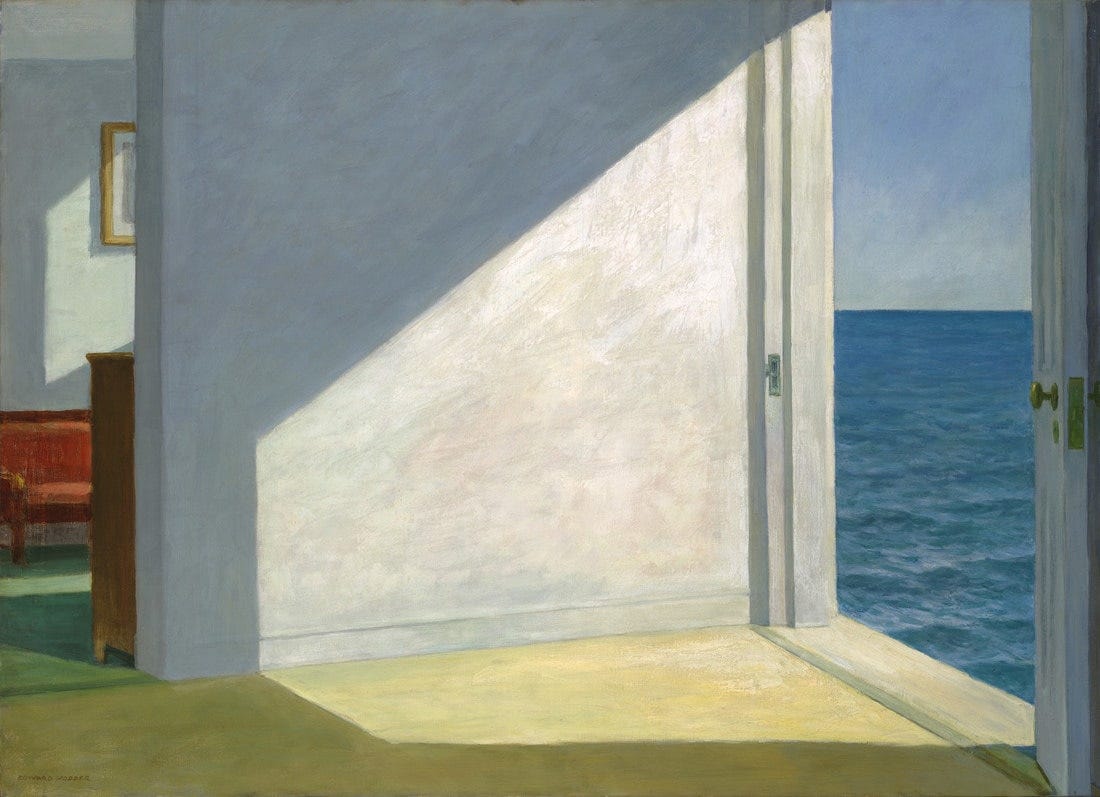

4. The Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard

“Great images have both a history and a prehistory; they are always a blend of memory and legend, with the result that we never experience an image directly… Consequently, it is not until late in life that we really revere an image, when we discover that its roots plunge well beyond the history that is fixed in our memories. In the realm of absolute imagination, we remain young late in life. But we must lose our earthly Paradise in order actually to live in it, to experience it in the reality of its images, in the absolute sublimation that transcends all passion.”

To be human is to float in the nostalgia of memory: memories of original homes, the small intimacies of boredom felt in childhood, the protections felt by the nests you remember. Bachelard doesn’t beat around the bush here. “Transcending our memories of all the houses in which we have found shelter, above and beyond all the houses we have dreamed we lived in, can we isolate an intimate, concrete essence that would be a justification of the uncommon value of all of our images of protected intimacy?”

This is the project of his book, here, and his answer is simple: like a good poem, “the house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.”

Existentialism poses the question of being “cast out into the world,” but what about those times in which we are in the interiors of our own home? Bachelard charts the course towards daydream through rafters, drawers, chests, cabinets, windows, cupboards, lamps, floors, attics, and cellars, — all of these small everyday artifacts, once considered as unintentional expressions of our shared capacity towards protection, towards safety, towards dreams, become points of understanding ourselves and our needs.

The book is heady, sure, but I still believe it to be an extremely approachable entrance to understanding not just interior design and architecture, but also poetry itself and how it works to give space to space to daydream in its whitespace and in its passionate connection to the everyday.

Very literally, The Poetics of Space forever changed the way I view my personal space and singlehandedly made these apartments I’ve lived in haphazardly for these first six years of my adult life into homes proper.

5. Collected Essays by James Baldwin

“Any real change implies the breakup of the world as one has always known it, the loss of all that gave one an identity, the end of safety. And at such a moment, unable to see and not daring to imagine what the future will now bring forth, one clings to what one knew, or thought one knew; to what one possessed or dreamed that one possessed. Yet, it is only when a man is able, without bitterness or self-pity, to surrender a dream he has long cherished or a privilege he has long possessed that he is set free—he has set himself free—for higher dreams, for greater privileges… It is one of the irreducible facts of life.”

- Faulkner and Desegregation, Baldwin

I initially approached Baldwin after I had poured over Rankine’s Citizen, Danez Smith’s poetry, and Malcolm X’s autobiography for a couple of months while going out along State Street, in Madison, for the George Floyd protests, — where I was tear-gassed once, but not too severely, — and came to Baldwin’s table thinking it could further expand my scope. This was absolutely the case. But I hadn’t expected to encounter such a beautiful and complicated portrait of a father-son relationship in Notes of a Native Son. I hadn’t expected such a fascinating, complicated portrait of MLK and Malcolm X. I hadn’t expected passionate essays on Faulkner and Feudalism. I hadn’t expected such intensely accurate analyses of American propaganda.

Baldwin’s one of those rare political writers who touched on everything as a part of the same struggle against the same powers; but his scope was broadened out not by apathy or cynicism but by a boundless empathy. If you are going to get your political compass from anywhere, James Baldwin is one of the best.

6. On Being Blue by William Gass

“Blue pencils, blue noses, blue movies, laws, blue legs and stockings, the language of birds, and bees, and flowers as sung by longshoremen.”

- On Being Blue, William Gass

What is blue? That’s the central question of this 100 page “philosophical inquiry” by William Gass that spends much of its page count simply listing various things that fit the description. Very much in the same vein as Maggie Nelson's Bluets, it poses the question of blue as one asked by our instinctual, literary, and sexual desires all bound together.

Is blue what it is because of the sky? What makes Singing The Blues blue if one cannot sing a color? Can one sing a color? Does the word blue come from a bruise having blue inside of it? Is blue the true color of shadows? Is blue the color of our romantic desires? Or are our romantic desires coming tied to that hazy blue of the open sky? Many questions to ask, and as a color is more an ethereal concept in the mind’s eye than it is a real, concrete thing to hold onto; the answers can span the whole breadth of human existence so bookended on all sides by colors and hues, murk and atmospheric desires, that we can't help but feel inside this pigment, or a figment of a pigment, which we've made up.

7. Understanding Media by Marshall McLuhan

“The electric light is pure information. It is a medium without a message, as it were, unless it is used to spell out some verbal ad or name. This fact, characteristic of all media, means that the "content" of any medium is always another medium. The content of writing is speech, just as the written word is the content of print, and print is the content of the telegraph. If it is asked, "What is the content of speech?," it is necessary to say, "It is an actual process of thought, which is in itself nonverbal.”… the "message" of any medium or technology is the change of scale or pace or pattern that it introduces into human affairs.”

John Carpenter’s They Live revolves around a pair of unassuming sunglasses which lets our burly, sweaty 80s working-class hero to fully see, for the first time, the extraterrestrials that control human society. McLuhan’s Understanding Media is another unassuming object, something you can read and then look around, startled by the sudden feeling that everything was not as you thought.

After flipping through its pages, the landscape of modern life makes sense through its lens, the book squares the circle, the book is a cardboard box full of puzzle pieces that are suddenly available to put together for the first time.

Is a lightbulb a medium? How does radio preclude fascism? How do newspapers and television affect a person’s worldview? What kind of information does the medium itself hold?—if you watch the same film on an iPhone versus a movie theater screen, is that the same movie? Or is it inherently different? Every paragraph in McLuhan's little book here has somewhere between three and ten hot takes, thrown out with such confidence and velocity that I forget I'm reading words and I feel like I need to dodge out of the way.

McLuhan came up with the phrase “The Medium is the Message,” and I’m certain you’ve heard his name before, — there are jokes about him in The Sopranos. But in the end, reading his work represents also one of the most effective ways to protect yourself against an increasingly fracturing modern media landscape.

8. The Golden Fruits by Nathalie Sarraute

“And that sudden squall… that enormous gust of wind… All lights out. Black night. Where are you? Answer. We’re both here. Listen. I’ll call out, answer me. Just so that I may know that you are still there. I am shouting in your direction with all my might. The Golden Fruits… do you hear me? What did you think of it? It’s good, isn’t it? And a dreary voice replies… ‘The Golden Fruits… it’s good…’”

Whooboy this is a hard translation to find in print. From what I can tell The Golden Fruits hasn’t been reprinted in English since the 1960s and what a shame that is! It’s such a fascinating look at a literary culture and such a fascinating approach to the novelistic form. There’s no real narrator and no real characters, only about 150 pages of overhearing dialogue at a café over the course of a couple of weeks while a frenzy grows about a renowned author’s baffling new novel The Golden Fruits (cough cough Intermezzo), one which the players in this small but contentious café circuit cannot seem to decide is profound or reductive, a masterpiece or a dumpster fire.

The book in question, the mysterious, elusive Golden Fruits is initially acclaimed, celebrated, and partied around in overheard conversation as a literary signifier, — “I read it, yup,—let me tell you, it was amazzzing.” — until an inevitable backlash begins to foment. And then comes a backlash to the backlash. And vice versa again. "Is The Golden Fruits overrated?" And suddenly the conversation becomes just that — “Isn’t the Golden Fruits so overrated? I’m so sick of hearing about The Golden Fruits.” And so the novel, never seen or really discussed in depth in the Sarraute’s narrative (and may in fact be the book you’re reading in your hands), evolves into something strange and unexpected among its readers.

Anyways, the book is a good example of one that’s experimental in style but still deftly approachable, satirical but never cruel. It’s a wonderful achievement and here’s hoping that some small printing press brings it back into print at some point, — if anyone from the NYRB is reading this (and I know some of you publishing people read Elle’s blog lol), please please please. I promise you it's so good. It's also available on Internet Archive, so I guess there's that too.

The first time I read it was an original printing from the UW Library and there had been so many generations of love poured all over the pages. Scribblings here and annotations here, exclamation points drawn by the funny bits and underlinings under the profound pins and needles of a good line or two. And then an odd feeling: whoever read this, the nameless pen strokes and small notes, they had liked The Golden Fruits too. In a way we’re exactly the people described in the novel, only separated by the years.

9. The Selected Writings of Gertrude Stein by Gertrude Stein

“A kind in glass and a cousin, a spectacle and nothing strange a single hurt color and an arrangement in a system to pointing. All this and not ordinary, not unordered in not resembling. The difference is spreading.”

- A Carafe, that is a Blind Glass, Gertrude Stein

A person writes when they write when they write. And you can tell that a person writes when want to be writing because they write. Stein is a writer whose first name is Gertrude who writes when she wants to be writing. Gertrude Stein writes when she writes and when she wants to be writing she writes writing like this writing I am now writing to you because I too am wanting to be writing to you and so I write writing to you like I want to be writing. Sometimes Gertrude writes like this. Sometimes she writes like she writes something else. She writes when she writes. Read when you Read. Be when you are. That is all.

10. The Waves by Virginia Woolf

"The sun had not yet risen. The sea was indistinguishable from the sky, except that the sea was slightly creased as if a cloth had wrinkles in it. Gradually as the sky whitened a dark line lay on the horizon dividing the sea from the sky and the grey cloth became barred with thick strokes moving, one after another, beneath the surface, following each other, pursuing each other, perpetually."

I'm finishing off this list with The Waves, in part because I know that Elle’s jealous of my HBJ copy with the incredible cover art, and in part because this book changed my life and the way I approach narrative.

Any lifetime is time spent on a shoreline of the real. Waves of small moments approach and dissipate across the sand, across the mind. Woolf has a thing for looking out over water, — it's a motif which returns over and over again in her works, — only this time there's no lighthouse on the other side, only more water. There is no false hope towards meaning except that for that surly false hope of hope in itself. The waves take the place of the lighthouse. Meaning is the yearning.

Here, in The Waves, we have an impressionistic portrait of six characters from their earliest days in the haze of childhood trying to understand themselves and the world; and resolving as the cruel ravages of the sunset begin to descend, the world going dark and connections loosening, hopes degrade in the face of time, in the face of the sun setting. She's painting a portrait of lives lived, from beginning to end, with an elaborate and unreal palette of colors impossible to see by the eye but easily seen by the heart.

The Waves is a constant companion for me, — there are a handful of books I read every year, — I read The Waves every June.

interlude i: what i read this week

I’ve been traveling, so I haven’t been reading or watching much!

Here are some article links you should read this week:

Flowers for Yellow Chins, Bruised Eyes, Forsaken Nymphs, and Impending Death

“Once you start knowing the names of plants, your landscape changes entirely.”

‘Social Studies,’ a documentary series by Lauren Greenfield, follows a group of young people, and screen-records their phones, to capture how social media has reshaped their lives.

babbling b(r)ook: on Finnegan’s Wake

Impossible language in the most impossible of books.

“After years of insomnia, I threw off the effort to sleep and embraced the peculiar openness I found in the darkest hours”

I Finally Accepted Nothing Can Be Perfect

“I have no excuses left. I’ve organised my notes, tidied up my desk, made coffee. Now I really need to start working on this piece. To be honest, I don’t really want to – the idea is sort of appealing in theory, but a lot less fun in practice.”

“A key difference to understand between boyhood and girlhood is that a person can only really understand boyhood for what it was once they’ve left it behind.”

Henri Matisse: ‘Is Not Love the Origin of All Creation?’

“The first step towards creation is to see everything as it really is, and that demands a constant effort. To create is to express what we have within ourselves. Every creative effort comes from within.”

interlude ii: what i watched this week

I rewatched Aftersun (for the sixth time—absolutely insane stuff), but it was with a friend who had never watched the movie, so I’m allowing myself to do so. I also watched We Live In Time in the theaters, which I actually didn’t love (or cry) as much as I thought I would. I rewatched Mamma Mia as well, which is always such a delight.

postlude

things i love: traveling, seeing my best friends for the first time in years, gin and tonics, autumn leaves, my ralph lauren dog sweater, charming independent bookstores

who is briffin glue substack

If the 3 I know (Bachelard, McLuhan and Sarraute) are anything to go by, I’ll have to check the others on the list. Eclectic!