shakespearean tragedies [nov week one syllabus]

books, lectures, essays, podcasts, movies, and video essays for the week

Weekly syllabus posts are back! I tried it out for a month in September and a lot of you requested that I do these consistently, so here is my plan for this week.

I have way more free time on my hands these days, so in my continued attempt to fix my attention span and gradual short form content induced brain-rot (and hopefully distract my brain which always spirals when I have any sort of free-thinking time during a depressive episode), I thought I’d plan a weekly syllabus. Here’s a collection of books, essays, podcasts, movies, video essays, and online lectures I’m interested in looking at this week, along with a recap of last week’s syllabus! I planned this thematically by each category.

Also, I have a special introduction/guide/syllabus to gothic fiction coming later this week so stay tuned for that!

playlist of the week

books

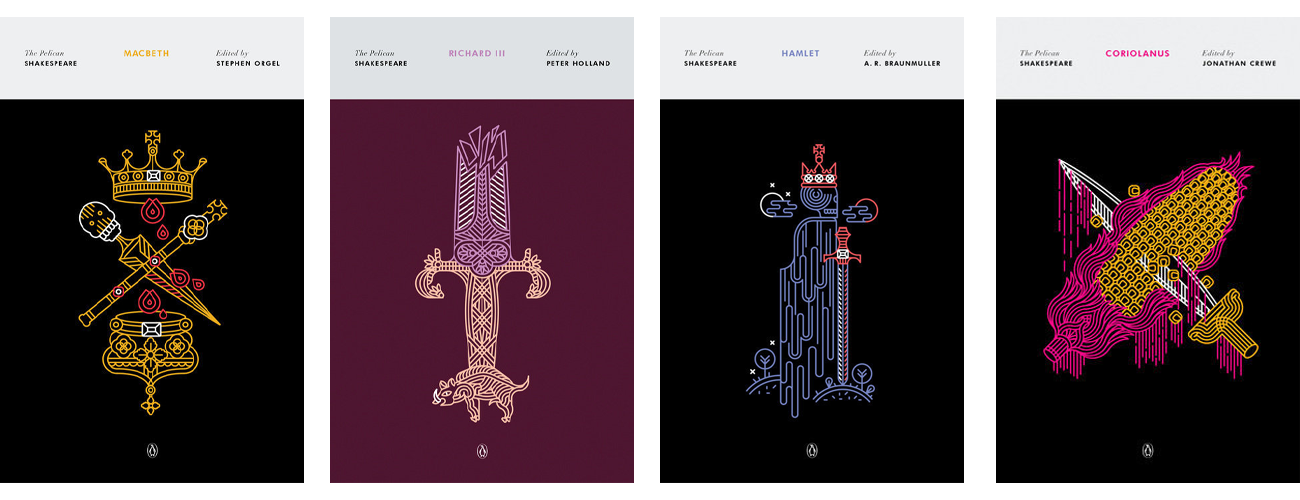

Main focus: Shakespearean tragedies. I reread Hamlet a week ago and realized how much I missed Shakespeare. Here is what I wrote in my syllabus example in my most recent post about tragedies written during this time:

“Elizabethan tragedies are slightly different than Greek/Aristotelian tragedies, which includes the five traits a tragic hero must have: being of noble birth, hamartia (having a fatal flaw), peripetia (a reversal of fortune), anagnorisis (tragic recognition), and catharsis. Two examples of this are Oedipus Rex and Medea. Elizabethan approaches to tragedies slightly different in that the downfall of the tragic hero is usually entirely contingent upon the hero’s fatal flaw. There is no chorus or an impartial moral body to move the narrative along.

Moreover, Shakespeare puts more of a focus on the tragic hero’s free will than Greek tragedies, in which the reversal of fortune mostly rely on the gods. While Shakespearean tragedies often include some sort of prophecy (the witches in Macbeth, for example), it is not as clear cut of whether or not it is fate or some sort of confirmation bias.”

The following reads are all rereads, but I wanted to read them back to back in this exact order (because I’ve never done this before). The plays are pretty easy to get through once you get the hang of Shakespeare’s language and rhythm. All of the four plays below are tragedies in their own way, with all of them being ‘fictional’ other than Richard III (which is a part of Shakespeare’s second tetralogy). You can see the difference in the complexities of the antihero/villain/tragic hero while making distinctions between the three, as his tragedies include one of the three as the main character.

One tip I’d advise to look out for is think about what Shakespeare is trying to say about performance and art in general and look at what is said in a speech that people can hear versus in an aside. It’s always fun differentiating this play by play.